Over the years many poultry fanciers, exhibitors, and breeders have witnessed a decline in the number and quality of certain breeds of poultry being exhibited in shows around the United States. This trend is occurring at an alarming rate in the UK and Europe and other countries, as well. Genetic diversity among these finishing flocks threatens the vitality and the future of these breeds.

Heritage Turkeys at Moss Mountain Farm

There’s always a lot going on at Moss Mountain Farm home of the heritage Poultry and Conservancy this time of year. Even though we had an arctic blast in February and it seems to slow things down suddenly as temperatures warmed and more sunshine blanket at the farm spring began to kick in high gear very quickly.

My internal farmer clock seems to always remind me toward the end of March and early April that I should be looking for turkey eggs, but this year they started coming much sooner. Presently at Moss Mountain Farm, a Heritage Poultry Conservancy maintains seven colors of heritage turkeys. This past Sunday I had a great time walking through the pens looking for eggs and grabbed a few photographs of some of our flocks. They were all loving the warm temperatures and radiate sunshine. What a beautiful day!

Black Spanish Turkey

Narragansett Turkey

Royal Palm Turkey

White Holland Turkey

Burbon Red Turkey

Heritage Bronze Turkey

As you can imagine the Tom’s are constantly strutting this time of the year as they vie for attention from their female suitors … and it’s hilarious when one Tom Gobble’s there’s a whole chorus of gobbling that follows. Our many visitors who walk the farm always enjoy seeing and hearing this display of a part of farm life that is now almost forgotten.

We mark all of our turkey eggs by the breed pen Number and color as we gather them from the nests. Then each 7 to 8 days we set the eggs in the incubators. It takes four weeks or 28 days to hatch a baby turkey or poult. They’re adorable and curious little creatures... and so friendly.

More later when our first poults hatch in the weeks ahead...

Derbyshire Redcap

The Redcap is a medium-sized bird that was traditionally valued as an egg producer. The skin is white and the eggshells are also white. They are only recognized in one color pattern, that is unique to the breed, and they were admitted to the American Poultry Association’s (APA) Standard of Perfection in 1888.

Standard Weights

Cock: 7.5 lbs.

Hen: 6 lbs.

Cockerel: 6 lbs.

Pullet: 5 lbs.

In Shape the Redcap resembles a heavy egg-type breed, with the body being long, fairly broad and moderately deep. The back is long, broad, and slopes somewhat to the tail, with the tail itself being well-spread and carried at an angle of 45-50°. The breast is broad, prominent and carried up, with the legs being somewhat long and set well apart. The rose comb, which is probably this breed’s most striking feature, is large, wide, and covered with long rounded protuberances and it terminates in a long well-developed spike.

The color pattern of this breed is not found on any other standard breed. In the male, the hackle is black with each feather being edged with red, with the entire feather shading to black at the base. The back is red with the saddles being red striped with black. The wing bows are solid red while the covert feathers are red tipped with a black half-moon spangle. The breast, tail, and body are all black. In the female the hackle feathers are black laced with golden bay. The back, wing fronts, wing bows, breast, tail coverts and body are all rich brown with each feather ending in a black half-moon spangle, while the tail is black. The shanks, feet, and toes, in both the male and female are dark blue while the beak is horn colored. The comb, wattles, face, and earlobes are all supposed to be red. This makes the Redcap one of the few breeds that has red earlobes but lays a white egg.

The Redcap was known by several names over the course of its history including Derbyshire Redcap, Moss Pheasant, and Manchester, with the Redcap part of the name coming from its very large rose comb. It was described by English writers of nearly 100 years ago as comparable to the Golden Spangled Hamburg, and in fact may be closely related to it. Though no positive connection can be made, some Redcap breeders of the late 1800’s believed the Redcap was a result of a cross between Old English Games and Golden Spangled Hamburgs. On the contrary some believed that the Redcap is an older breed than the Golden Spangled Hamburg. Which suggests that the breed is hundreds of years old. Still another theory would suggest that the Golden Spangled Hamburg and the Redcap were developed at the same time and the two types were just selected in two different directions, leading to two very different breeds.

Though no one is 100% sure of the origin of the Redcap, it was at one time very popular in Yorkshire County, particularly around Derbyshire. In fact, Mr. W.H. Baker, a prominent Redcap breeder in the 1920’s and 30’s said that half of the Redcap breeders in the world lived within 10 miles of Derbyshire. Moreover, in Derbyshire they were for a long time considered an excellent and profitable utility breed, and were it not for the breeders in this area, the breed would have become extinct in the early 1900’s. Part of the reason for the breeds decline was the emphasis that breeders put on large combs. Many exhibitors developed the breed’s comb to be exceptionally large and grotesque in appearance, while neglecting the breed’s utility qualities. However, a breed club was eventually organized to revive the Redcap. However, today, the Redcap remains somewhat rare in its home country.

It is not known when the Redcap was first brought to the United States. What we do know is that the breed appears to have been widely distributed in the U.S. before 1870. Additionally, some sources have said that it is possible that the “Red Dorkings” entered in the earliest poultry shows were actually Redcaps. If this is so then that would place the Redcap as being in the U.S. since well before 1870. Whatever the case may be, it is known that until the 1890’s many large flocks of Redcaps were kept for layers by farmers and poultry specialists alike. However, in a few years the breed almost completely disappeared, and to this day is still very rare. Redcaps are rarely seen even at our largest shows, this is one breed that is in very desperate need of more supporters.

As a bird for the home flock the Redcap would make a good choice, where a somewhat heavier egg breed is desired. The females are good layers and historically were said to lay up to 200+ large eggs a year. The hens rarely go broody and they are athletic and active foragers. However, due to to this active nature they may require a higher fence or one with a cover in order to contain them to certain areas. Furthermore, thanks to their larger size the extra cockerels could make good table-birds.

Bantam Redcaps

(Rose Comb Clean Legged class)

Both the APA and American Bantam Association (ABA) recognize the bantam Redcap. The ABA however lists the breed on its “inactive” list. This is simply a list of breeds the organization still recognizes but due to a lack of interest in the breed they do not publish a full description in their Bantam Standard. Shape and color requirements are the same as for large fowl and also like the large fowl the bantam Redcap is very rare, if it even still exists.

Standard Weights

Cock: 30 oz.

Hen: 26 oz.

Cockerel: 26 oz.

Pullet: 24 oz.

Prepared by Michael Schlumbohm

References

Robinson, John H. Popular Breeds of Domestic Poultry. Dayton: Reliable Poultry Journal, 1924.

Brown, Edward. Races of Domestic Poultry. Liss: Nimrod Book Services, 1985.

Scrivener, David. Poultry Breeds and Management an Introductory Guide. Norfolk: The Crowood Press, 2008.

Dohner, Janet V. The Encyclopedia of Historic and Endangered Livestock and Poultry Breeds. New Haven: Yale University, 2001.

The American Standard of Perfection Illustrated: A Complete Description of All Recognized Breeds and Varieties of Domestic Poultry. Burgettstown, PA: American Poultry Association, 2010.

Bantam Standard for the Breeder, Exhibitor, and Judge. 2011 ed. Kansas City: Covington Group, 2011.

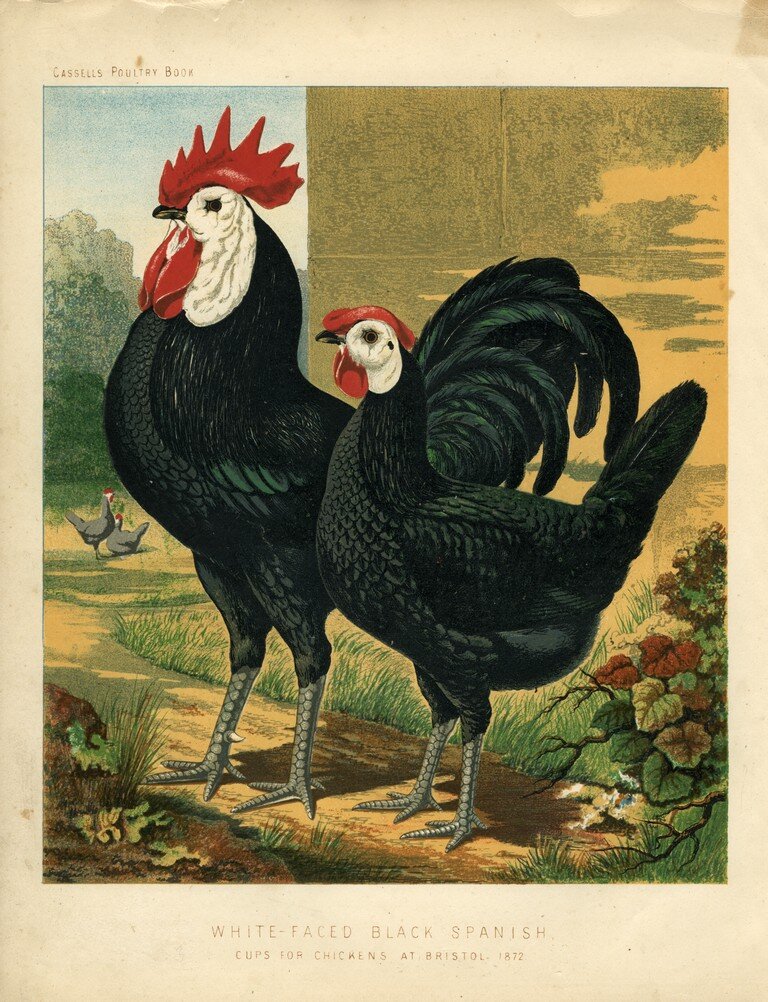

White Face Black Spanish

What moves a person to become a dedicated breeder?

Stories about the conservation of breeds can often be dry, if not dull, but more often than not when you get to the passion at its core stories can become powerful and engaging, contagious even. The intention and the goal of supporting threatened breeds is a noble one, but it’s the people along the way that one encounters and the challenges they meet that makes the effort interesting and inspiring.

White Face Black Spanish

We began a journey seven years ago looking for White Face Black Spanish at the encouragement of Dr. Keith Bramwell and Frank Reese. It had become clear by speaking to a few APA judges, conservationist that this great foundational breed was in trouble.

We have all heard the reasons about the decline in standard bred large fowl; few breeders are now focused on them, the flocks are small, feed is expensive and fewer have the time and space to focus on them. As a result, viable breeding populations with genetic diversity are diminishing.

White Face Black Spanish chickens are a fowl with ancient origins. It seems certain that they date back to at least the Roman conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, but likely much earlier. Scholars believe Phoenician traders were responsible for much trade and disbursement of goods and livestock much earlier than previously recognized. They became an important foundational breed to the Mediterranean class of fowl and through the mists of time continue to capture us with their striking appearance and generous egg production.

White Face Black Spanish

Seven years ago our flock of White Face Black Spanish came to us at Moss Mountain Farm through Jim Bell, a dedicated and knowledgeable keeper of poultry in eastern Tennessee. When I first met Jim he had kept a flock of large fowl Spanish for 38 consistent years. As he recounted to me, he was a kid always interested in poultry. His father recognized this and told Jim at 9 years old to go through a local poultry show and choose any breed he wanted. Jim did just that. When he saw for the first in his life the strikingly beautiful large fowl White Spanish on display he knew without hesitation in that moment that this was the breed for him. He shared this story with the same enthusiasm he must have had when he first brought birds home. Jim kept Spanish and continued to improve them for the next 39 years. His story inspired and continues to inspire me.

We were fortunate to get to know Jim, for many reasons. His kind, earnest and gentle manner was refreshing. His dedication to the conservation of breeds as well as his family farm naturally drew you into him.

White Face Black Spanish and P. Allen Smith

First, we received a generous batch of Spanish eggs that were picked up and brought to Arkansas by Carroll Moreland on March 1, 2013. Carroll, upon arrival at Jim’s place, was taken by Jim and the care he took of his family’s farm and his flocks. Carroll brought the eggs and enthusiasm for Jim’s work to Moss Mountain Farm. As luck would have it, we had a less than a stellar hatch from the eggs due to an incubator mishap, but what few hatched flourished.

I must admit I was slightly disheartened by the meager flock we had managed to get going with the eggs when Jim on a phone call one day said ‘well, why don’t you just let me hatch you a pen of these’, and he did. That’s how we came to keep Spanish today. Since then we have only outcrossed them once with a male sent to us by Lew Wallace who, at the time, was keeping some of Duane Urch’s line. The outcross was nothing short of explosive.

But, from where do those outcrosses come in the future? And where are the breeders of the future who are so passionate about a breed that they keep them for 39 years? A year after we had a solid flock established Jim shared with me that someone or persons had come on to his farm and stolen his entire flock of Spanish. He had unwittingly shared images of his birds and the location of his farm on Facebook, such as many of us do, and then they were taken from him.

Black Face White Spanish when shocked about the news of Jim’s flock.

Such a loss is bewildering and devastating; heightened by all of the years of dedication. I asked Jim, time and again, if we could get birds back to him to restore his flock. He refused. He had lost something more than the birds themselves. We lost a dedicated advocate of a fragile breed. This was and continues to be very hard to accept.

I give Jim Bell credit for the conservation of a line of such an important breed. Jim is one of those grounded, silent stewards who is a champion that has worked tirelessly to perpetuate a breed out of passion and a deep desire to see the breed prosper. I’m sure similar stories abound. We just need more knowledgeable and committed enthusiasts like Jim, now and in the future.

The Heritage Poultry Conservancy will support a heritage breed initiative at the Ohio National Show in 2020. For more information about the the Heritage Poultry Conservancy join us on Facebook at Chicken Chat.

Roman Tufted Geese

The Tufted Roman (Light Goose class) is a small, compact lightweight breed of goose that is characterized by a tuft of feathers on top of its head. The Tufted Roman is only recognized in white and was admitted to the American Poultry Association’s (APA) Standard of Perfection in 1977.

The standard weights are as follows:

Old Gander: 12 lbs.

Old Goose: 10 lbs.

Young Gander: 10 lbs.

Young Goose: 9 lbs.

The body of the Tufted Roman is rather short and plump with a well-fleshed carcass and fine bones. The paunch is dual lobed and should be held tight and close to the body with little tendency to sag. Keep in mind, however, that females just prior to and during egg production will have enlarged paunches. The back is medium in width and should be about twice as long as it is broad, while the breast is full and well rounded. The neck is moderately long and stout with a slight arch. The breed’s most notable feature is the cylindrical tuft of feathers located on the crown which starts at a line even with the back of the eyes and inclines backward. The plumage is pure white while the bill is pinkish to reddish-orange and the shanks and feet are orange to pinkish-orange. The eyes are bright blue.

The ancestor of our modern Tufted Roman is, at least in part, the non-tufted Roman that was once very common in Italy as well as southern and central Europe. These non-tufted geese were characterized by their small size and compact plump bodies very similar to the Tufted Romans we see today. This original non-tufted Roman ancestor is believed to be a very old landrace breed. In fact, small white geese have been known in Italy for 2,000 years and were revered by the people as sacred animals of the god Juno (the goddess of marriage). These small white geese were eventually spread to the rest of Europe by the Roman armies and became well-known throughout the continent. It is not known when the first tufted birds appeared in the breed, but literature of the early 1900’s, cites that many Roman geese had a small crest at the back of the head.

Some waterfowl authors believe this is not the only possible explanation of the origin of the modern Tufted Roman. Well-known waterfowl authority Oscar Grow suggested that tufts, like crests in ducks, can show up in any breed, particularly in English and German geese, and it is from these various tufted birds that the Tufted Roman descended from. Grow reasoned that because many early American tufted geese more closely resembled English birds in terms of body shape and size rather than the original non-tufted Roman that the breed should not have been called Roman.

However, other authors of later years have argued that most tufted geese in the United States did, in fact, resemble the old non-tufted Roman in terms of size, body shape, and color and therefore deserved the designation Roman in the name. It was further argued that these birds had the same temperament and egg-laying ability as the non-tufted Roman. With this assertion and the fact that tufted Roman geese have been described since the early 1900s, it is probably safe to guess that our modern Tufted Romans are the result of a mutation that occurred in non-tufted Romans. However, it is still not out of the question that other tufted geese may have been crossed into these birds and were then bred back to Roman breed characteristics.

There are no clear records indicating when the first Romans were first imported to the United States. What we do know for a fact is that Richard Gidley, of Salem, Ohio imported some in the 1930s and for over 40 years he bred and distributed this breed all over the United States.

In this country, Tufted Romans never made it as a commercial breed as they do not have the size or growth rate as the heavyweight breeds. However, in Europe there are many strains of commercial geese that are designated as “White Italian” these are typically valued for their high egg production. Their relationship to our Tufted Roman isn’t certain but it is possible that they share a common ancestor, the original non-tufted Roman. This could indicate the Tufted Roman’s potential to be better utilized as a meat production bird if the right selection pressures for high egg production are applied.

As far as the breed’s history and purpose in this country, their niche has primarily been as an exhibition bird kept by fanciers. Nonetheless, the Tufted Roman is still a suitable bird for those wishing to produce a small market goose. As a bird for the homesteader, they make a good choice because of their small size and active foraging ability. They also make excellent natural parents and can easily raise their own broods. Moreover, they have a generally friendly nature and are easy to handle. In a flock mating situation, one gander can usually cover two to four females.

If a person has an interest in using, breeding, and preserving true Tufted Roman geese there are a few things to keep in mind when selecting breeding stock. Many people make the mistake of calling any goose with a tuft a Tufted Roman. This is simply not the case and many unscrupulous sellers take advantage of this. In order to select a true Tufted Roman first, look for birds with the appropriate body shape and size. Avoid choosing individuals that are oversized, too tall or long-bodied, are too slender, or have heavy low-slung paunches. These traits are usually an indication of cross-breeding. Other physical deformities to watch out for are bowed or kinked necks, or small tufts. Color-wise, avoid ganders and old (over one year old) geese with too much gray in their plumage. Keep in mind, however, that it is perfectly normal for young Tufted Romans, especially females, to have traces of gray in the wings, back and occasionally the head. This gray color usually disappears after their first molt. Also, avoid birds with bright orange bills and legs. The Standard of Perfection calls for reddish-pink shading in the bill and the legs. Bright orange legs and bills are a serious fault in the show ring and should be selected against. It should also be noted that there are now buff and gray geese that have tufts. These birds are not Tufted Romans. These are merely colored birds that have been crossed with Tufted Romans or are the result of a mutation that occurred in a colored goose breed and should not be confused with the true APA recognized Tufted Roman. Non-Tufted Romans do exist in this country, however, they are not nearly as common as their tufted counterparts. The APA does not recognize these non-tufted birds.

Tufted Romans can typically be seen at most poultry shows across the country and are normally represented in small (one to five bird) classes. Conditioning Tufted Romans for the exhibition is a relatively simple matter. They just require bathing water to keep themselves clean and dry, mud-free quarters to keep their plumage from getting stained.

In summary, the Tufted Roman makes a fine goose for the homesteader wishing to produce a small, plump market bird. Their tufts along with their small compact build and reddish-pink bills and legs make them unique among geese. This breed has much potential as a meat producer for the small farm and as an exhibition bird for the hobbyist.

Prepared by Michael Schlumbohm.

References

Brown, Edward. Races of Domestic Poultry. Liss: Nimrod Book Services, 1985.

The American Standard of Perfection Illustrated: A Complete Description of All Recognized Breeds and Varieties of Domestic Poultry. Burgettstown, PA: American Poultry Association, 2010.

Sheraw, Darrel, and Loyl Stromberg. Successful Duck & Goose Raising. Pine River, MN: Stromberg Pub., 1975.

Grow, Oscar. Modern Waterfowl Management and Breeding Guide. N.p.: American Bantam Association, 1994.

Holderread, Dave. The Book of Geese a Complete Guide to Raising the Home Flock. Corvallis, OR: Henhouse Publications, 1993.

“Roman Goose.” N.p., n.d. Web. 10 July 2014. <http://www.livestockconservancy.org/index.php/heritage/internal/roman>.

Toulouse Geese

Gray Dewlep Toulouse

The Toulouse (Heavy Goose class) is a heavy breed of goose originally developed for meat and liver production. The American Poultry Association (APA) recognizes the Toulouse in two varieties, the Gray, which is the original variety, and the Buff.

Standard Weights

Old Gander: 26 lbs.

Goose: 20 lbs.

Young Gander: 20 lbs.

Young Goose: 16 lbs.

The Toulouse at one time was considered an excellent meat breed. It is in the heavy class and along with the Embden possesses the largest standard weights of any breed of goose. The Toulouse is a massive and imposing breed of goose. The head is large, oval-shaped and wide with a dewlap that stretches from the bottom of the jaw, at the junction of the bill and throat, and attaches to the neck. The body of the bird is wide, long, and very deep. The breast is wide, prominent and smoothly attaches to the keel which nearly drags the ground. This keel runs in a smooth unbroken line to the legs. The stern of the Toulouse is deep and square and should have two well-balanced lobes. The overall impression is of a large, deep, rectangular bird. Another unique feature of the Toulouse is that the feathers of the back should have a ruffled appearance rather than being smooth like most other breeds of geese.

In color, the gray Toulouse is an even soft gray with each feather of the back and flanks being edged with near white, with the rump being white. The Buff Toulouse should be an even shade of buff with each feather of the back and flank edged with nearly white, the rump is also white. The bill, legs, and feet of both varieties are orange and the eyes are brown.

Gray Dewlep Toulouse

Gray recognized in 1874

The breed takes its name from the city of Toulouse in southern France. The geese in the vicinity of this city were famous for size and productivity since the beginning of the nineteenth century, but whether these qualities were recent developments or characteristics of the local geese of this area from much earlier times is unknown. Though known by repute in England as early as 1810, Toulouse geese were not imported into that country until about 1840, when the Earl of Derby imported them to add to his poultry collection at Knowsley.

So far as can be learned from available records, Toulouse was first shown in America at Albany, New York, in 1856. This relatively late date of importation makes the Toulouse the latest of the “improved” breeds to be brought here, the other “improved” breeds being the Embden, African, and Chinese. From first acquaintance with it, the breed strongly attracted American fanciers and breeders and it soon became the most popular of the improved breeds.

Toulouse was originally bred for fast growth and for liver production, and are still bred and raised commercially in Europe primarily for pate de foi gras production. Additionally, Toulouse geese are and have always been known as prolific egg producers. Reports of up to 50-60 eggs per season are not uncommon. For this reason, in early America, and in England female Toulouse were often used to cross on Embden ganders with the resulting offspring then used for market geese. This cross would produce more goslings with lighter colored feathers and better carcass traits.

Today’s standard Toulouse, as bred for exhibition, was developed in England. These exhibition Toulouse which later became the standard Toulouse are characterized by large size, deep keels, and dewlaps. The plumage of the Toulouse is somewhat loose-fitting which often makes the birds look even larger than they actually weigh.

Buff Toulouse

Buff Recognized in 1977

The Buff Toulouse is said to have been produced from pure Toulouse stock by a Mr. Paul Lofland of Oregon. Since the first Buff Toulouse has been developed it is probable that the American Buff goose was crossed in with some strains of both Buff and Gray Toulouse to further establish the buff variety.

When looking to buy Toulouse geese buyers need to take some caution as to what they buy and where they buy it. Many so-called “Toulouse” in America are not the true standard type, but rather a smaller version that does not have the characteristic keel and dewlap. The only similarity between a standard Toulouse goose and what many hatcheries sell as “Toulouse” is the color. When looking for a true Toulouse it is best to go to a reputable breeder and be sure the stock is of good size and has the characteristic keel and dewlap. When choosing breeding stock be sure to avoid birds with shallow and narrow heads, small dewlaps, narrow bodies, or under-developed keels. Keep in mind, however, that Toulouse takes a few years to fully develop. Young Toulouse often have smaller dewlaps and less developed keels compared to mature specimens. Color faults to avoid include white feathers under and around the bill or indistinct white edging on the flanks and back. In Buff Toulouse avoid geese that are an uneven shade of buff. Also, pay attention to the bill and leg color. Avoid birds with pinkish shading on the legs or bills. The dark color in the bills of mature specimens (over one-year-old) is a serious fault. However, most young Toulouse will show dark pigment on the tip of the bill. This is normal and usually disappears with age.

Caution needs to be taken when feeding Toulouse geese, as well as other heavy breeds, as they will get too fat if their diet is not watched. This can lead to a multitude of fertility and egg production problems. Many breeders restrict feed intake of their geese before the breeding season so that they lose body fat. This has a big impact on the appearance of the bird, as the keel will shrink some. As far as temperament goes the Toulouse is a very docile, quiet bird and not prone to aggressive behavior, except during breeding season where such behavior is normal for any breed of goose.

Toulouse are very good egg layers and it is possible to produce a lot of offspring from one mating in one season’s time. Toulouse are best mated in pairs or trios as the ganders are not particularly active breeders when compared to the medium and lightweight breeds. Though good fertility can be achieved on land, it sometimes enhances fertility if they do have the chance to mate in water. They are average foragers and like to graze but do not wander very far from where they eat and live. This could be advantageous for those who wish to let their geese roam but don’t have a lot of space for their birds or who have close neighbors.

Prepared by Michael Schlumbohm

References

Robinson, John H. Popular Breeds of Domestic Poultry. Dayton: Reliable Poultry Journal, 1924.

Brown, Edward. Races of Domestic Poultry. Liss: Nimrod Book Services, 1985.

The American Standard of Perfection Illustrated: A Complete Description of All Recognized Breeds and Varieties of Domestic Poultry. Burgettstown, PA: American Poultry Association, 2010.

Sheraw, Darrel, and Loyd Stromberg. Successful Duck & Goose Raising. Pine River, MN: Stromberg Pub., 1975.

Grow, Oscar. Modern Waterfowl Management and Breeding Guide. N.p.: American Bantam Association, 1994.

Sebastopol Geese

The Sebastopol (Medium Goose class) is a medium-sized goose best known for their curled feathers which is analogous to frizzling in chickens. White, the only recognized variety, was admitted to the American Poultry Association’s (APA) Standard of Perfection in 1938.

Standard Weights

Old Gander: 14 lbs.

Old Goose: 12 lbs.

Young Gander: 12 lbs.

Young Goose: 10 lbs.

This is the only breed of goose that has the characteristic curled feathers; even the flight and tail feathers are twisted. Not only are the feathers curled but they are also longer than the average goose feather. This added length adds to the overall impression of a profusely feathered bird. Sebastopols are medium in size and have somewhat rounded heads that appear large in proportion to the body. Due to the long, curled feathers their bodies look appear rounded. If one can look beneath the feathers, one will find a well-fleshed, compact bird with a somewhat short back and an oval plump body. It is said that a good Sebastopol should be able to sit in and fill a bushel basket. The Sebastopol should have dual lobes but they are hidden by the long, profuse feathering of the body. The thighs are short and well-muscled with the shanks also being short and stout. In general, the longer and more curled the feathers of the breast, back, and body the better. The plumage is pure white with the bill, shanks, and feet being orange while the eyes are bright blue.

This breed of goose is said to have been unknown to Western Europe until the time of the Crimean War, with the first birds reaching England around 1859. The name Sebastopol was given at that time. Reportedly the name came from a seaport located in southeastern Europe and it is likely this is where the first birds were shipped to England. Thus, they named the breed Sebastopol. Later they were also known as Danubian geese. Sebastopols are thought to have originated from the region of Southeastern Europe and eastern Russia. Later reports indicated that Sebastopols were, in fact, numerous in this area. It is not clear when the first Sebastopols were first introduced in the United States but it was known to have been here at least by the early 1920’s.

While chiefly distinguished by the peculiar development of the feathers (the characteristic which has made them of interest in Western Europe and America), they have other qualities which account for their considerable popularity in Eastern Europe. They have a quiet temperament, not apt to wander, yet good foragers, and easily fatten. The flesh is of excellent quality, they are moderate layers, and make good sitters and natural mothers. For these reasons, they were a popular utility bird in their homeland.

In this county, Sebastopols were always a fancier’s fowl and were never used to any extent for large-scale meat production. Because of their unique ornamental appearance, they were always and still are popular show birds. Many good quality birds can be seen in most of America’s shows. In fact, the Sebastopol class is usually the largest goose class of any breed.

Although the only recognized color of Sebastopols is White, there are many breeders now working with colored varieties. Gray, Buff, Blue, Gray Saddleback, and Buff Saddleback Sebastopols are now being seen more frequently.

Conditioning Sebastopols for show is more difficult than most other breeds of geese. Due to their long curled feathers, it is important to keep them in clean dry pens to avoid dirty and broken feathers. Some literature suggests allowing the birds constant access to bathing water in order to keep their white plumage clean. However, some people have recommended that Sebastopols should not be allowed constant access to swimming water because the feathers do not shed water like normal feathers and this can lead to a ragged appearance. What some recommend is putting them in an enclosure with moderately tall grass to keep them clean and only giving them five-gallon buckets of water to submerge their heads in. This keeps the body feathers dry while still allowing them to keep themselves clean. It is best to leave the choice of management up to the individual and let them decide which method gives the best results. Regardless of the method used, overcrowding must be avoided with this breed to keep the feathers clean and intact. If they are too crowded there is a tendency for the other birds in the pen to pull out each other’s long loose feathers.

When looking to purchase breeding or show birds there are some things to watch out for. First of all, avoid birds that have long, rectangular bodies. The body should be rounded when viewed from above and from the side. Avoid smooth breasts. Every feather on the breast should be curled and if this is not watched a large percentage of the offspring will end up being smooth breasted. Another major fault to avoid is stiff primary and secondary wing feathers. The primary and secondary wing feathers of Sebastopols should be long, soft and pliable allowing for maximum curl. Angel wing is a disqualification in any breed of goose, but many inexperienced Sebastopol owners easily miss this since it is harder to detect. Angel wing can be detected if the last joint of the wing points out away from the body at a sharp angle.

As far as color goes, avoid anything with large amounts of gray. Some young birds may show traces of gray, and this fine. This gray color usually disappears after their first molt, but in an adult, any traces of foreign color should be avoided. Proper bill, shank, foot, and eye color should also be kept in mind. Some Sebastopols have a tendency towards pink shading in the bills and legs.

Although Sebastopols are largely an ornamental, exhibition bird they could still be used a utility bird for home meat production. They produce a mid-sized well-fleshed carcass. The females lay well and make excellent natural mothers, while the ganders are fertile. One male can be kept with up to two to three females. Of course, their unique feathering makes for an interesting conversation piece.

Prepared by Michael Schlumbohm

References

Robinson, John H. Popular Breeds of Domestic Poultry. Dayton: Reliable Poultry Journal, 1924.

Brown, Edward. Races of Domestic Poultry. Liss: Nimrod Book Services, 1985.

The American Standard of Perfection Illustrated: A Complete Description of All Recognized Breeds and Varieties of Domestic Poultry. Burgettstown, PA: American Poultry Association, 2010.

Sheraw, Darrel, and Loyd Stromberg. Successful Duck & Goose Raising. Pine River, MN: Stromberg Pub., 1975.

Grow, Oscar. Modern Waterfowl Management and Breeding Guide. N.p.: American Bantam Association, 1994.

Sebastopol Geese at Poultryville

I want to tell you about what’s just hatched in the incubator. A beautiful little Sebastopol gosling. Sebastopol is a breed of geese with the curly feathers as adults. Their feathers have a little twist to them so the bird looks like a feather pillow. When they are little like the most recent hatchlings you can’t really tell that they will have that kind of hairdo, or, I should say, feather-do, but eventually, as they mature the feathers will curl.

Now when the goslings first hatch they don’t need any feed or water for up to 48 hours. There’s enough yolk still left in their systems that will supply energy and food for them. When it is time to give them water to drink, I like to give them a vitamin supplement too.

Next, we start them on a feed that is 20% protein. I also add a little brewer’s yeast to the feed because it gives them a little more niacin and they need that.

Once the goslings start eating you would not believe how much they will expand in just four weeks. They start going through that very awkward stage where they begin to lose their down and put on feathers. By six months they look like they’re full-grown.

I enjoy having geese at the Garden Home Retreat, particularly the rare Sebastopols, because it provides an opportunity for their genetics to be perpetuated, and also they’re very beautiful to have out in the pasture and on the pond.

Conservations Matters: Heritage Geese

Giant Dewlap Toulouse at Moss Mountain Farm

It’s well-founded that standard bred large fowl and quality breeders are in decline, and heritage breeds of geese are no exception. Many reasons are cited for this decline, such as the cost of maintaining flocks of such large birds, as well as the increasing challenges of processing waterfowl for the farm to table market.

At the August 2019 Large Fowl Summit held at Moss Mountain Farm, the Heritage Poultry Conservancy (HPC), American Poultry Association (APA), The Good Shepherd Conservancy, and the Livestock Conservancy (LC) agreed that December would be deemed "Heritage Goose Month.” HPC board member, Dr. Keith Bramwell, said ‘this effort is a way to raise awareness for the need for greater conservation work among geese breeds in need."

P. Allen Smith & a Sebastopol Goose

While some breeds, such as Africans and Sebastopols, enjoy popularity among exhibition breeders and the public, other breeds find themselves in more dire circumstances. Shetlands, Cotton Patch, Roman Tufted and Steinbachers are among those seldom seen in poultry shows, reflecting their small population status. The Livestock Conservancy maintains that six breeds are currently on the critical and threatened lists, meaning among those cited with critical status there may be fewer than 500 breeding birds in the United States, with five or fewer primary breeding flocks (50 birds or more), and an estimated global population of less than 1,000.

In an effort to conserve Saddleback Pomeranians and large Embdens, the Heritage Poultry Conservancy is working with Frank Reese at the Good Shepherd Conservancy to get these breeds back into production. Reese, well known for his work with Heritage turkey varieties, has plans to bring these two breeds of "market geese back to the market, where they belong," says Reese. P. Allen Smith and Frank Reese have been joining forces for the past 13 years to conserve heritage breeds of poultry. Moss Mountain Farm serves as a safe harbor site for some of Reese’s Heritage turkey, chicken and waterfowl genetics. Reese goes further to say ”we are about biodiversity and helping to change what we eat by better farming. Not only saving endangered poultry but bringing diversity to the culinary world. We are starting to get some great support both nationally and internationally."

P. Allen Smith & Frank Reese at Moss Mountain Farm, 2009

In December, the HPC will deliver approximately 65 Heritage geese for breeding stock to Reese’s farm as a 'boots on the ground' conservation effort. The Heritage goose bloodlines will come from a range of sources, including Moss Mountain Farm, Pete, and Cheri Dempsey, Michael Schlumbaum, No Fish Creek Farm, Gerald Donnelly, Holderread Waterfowl Farm, and others.

By producing large numbers of goslings each year and making selections from these populations, Reese will be able to make greater strides in improving the size, type, and vitality of the breeds, according to Smith. “These birds should be excellent market fowl and just as good in the exhibition ring. This was the approach and criteria taken in the past, there was no differentiation between market and show," said Reese.

Saddleback Pomeranian Geese at Moss Mountain Farm

Demand for market geese has declined over the years, but niche markets remain interested in sources for heritage breeds, especially when raised and processed ethically. December and the winter months in many cultures have traditionally been a time when the goose has been a part of culinary traditions, much like the turkey in November. Patrick Martins’s Heritage Foods USA is a key component of this conservation effort. Without the support and distribution of Heritage Foods USA, there would not be a nationwide effort to bring these birds back to the market. “Patrick’s dedication to helping save and support small farmers and heritage poultry overall is to be commended” stated Reese.

“Heritage Foods — the company at the forefront of the nonindustrial meat movement —

”

China Geese

Moss Mountain Farm, home of the Heritage Poultry Conservancy, maintains flocks of six breeds of geese; including Saddleback Pomeranian, Roman Tufted, Dewlap Toulouse, Sebastopol, Chinas and Embdens. The mission of the HPC is to raise awareness regarding these breeds, support youth engagement through exhibition awards, and conserve genetics. “We presently keep over 50 breeds and varieties of rare and endangered poultry for the purposes of genetic conservation,” said Smith.

Sebastopol Geese at Moss Mountain Farm

‘Boots on the ground’ efforts such as the recent National Heritage Turkey show sponsored by the HPC at the Ohio National was a huge success, said Clell Agler, “Almost 200 entries made it the largest show in decades." Smith, the founder of the HPC, was adamant that turkeys be bench judged as they were in the past, meaning exhibitors are required to bring their birds before the APA licensed judge. This is an attempt to close the gap between market quality and exhibition birds, advancing the Heritage farm to fork movement.

“Volunteers are critical in these conservation efforts.” cited Smith. Reese has many volunteers for turkey ‘loading’ days, usually the second weekend in November. Russ Crevoiserat, 70, a retired veteran and online accounting instructor for the University of Southern New Hampshire has logged over 2,400 miles this fall to collect flocks of geese for the Heritage Goose project. Other volunteers made up of poultry science students, breeders and small farm advocates all play their roles to accomplish these strides in Heritage poultry conservation.

Ohio National Turkey Show 2019 Draws Record Entries and Crowds

(Columbus, Ohio) The 62nd annual Ohio National Poultry Show took its organizers and the Heritage Poultry Conservancy by surprise with the participation in and enthusiasm for the heritage turkey show. “We knew it would be big, but never expected such a level of participation and excitement from exhibitors and attendees alike,” said Clell Agler, show chairman. Visitors from across the US, Canada, Finland, and the United Kingdom were in attendance.

The total number of turkey entries exceeded 180 birds. Each entry was bench judged by APA judge Jeff Halbach, requiring exhibitors to bring each of their birds to the judging table when called up by show officials. The judge, as in the past, examined each bird individually for its size, conformation and important market qualities.

The 2019 Turkey Show champion went to a Black Spanish old tom, exhibited by Chris McCary. Reserve champion and the Best display went to youth exhibitor Jonathan Woodward for an outstanding collection of Narragansett turkeys.

P. Allen Smith with his Black Chocolate Turkey

One of the goals of the Ohio National Turkey Show was to raise awareness for the need for greater conservation. “A new generation of quality heritage turkey breeders is essential to keep these national treasures in good stead, our hope is that this show will be the beginning of many,” said P. Allen Smith, founder of the Heritage Poultry Conservancy. In fact, as a way to further heighten interest in heritage turkeys, the Ohio National was asked to host the qualifying meet for the Chocolate Turkey variety to be officially recognized by the American Poultry Association (APA).

Mr. Jeff Halbach announced at end of the judging to the crowd gathered at the show that “from what I’ve seen here today among the Chocolates exhibited, these birds definitely should qualify for APA recognition and should be entered into the APA’s Standard of Perfection. The consistency of size, type and color was a complete and welcomed surprise to me."

Jeff Halbach inspecting closely as he judges the turkeys.

Zane Graham from Fall Fire Farm is to be credited with the efforts of bringing the Chocolate variety back into recent awareness. “This show brings us one step closer to having chocolates admitted into the APA," said Graham. Only one more APA sanctioned show in 2020 is needed with the required number of birds and exhibitors of chocolates to meet the APA requirements for inclusion. Chocolates were popular in certain regions of the South well before the Civil War. The last heritage turkey variety recognized by the APA was the Royal Palm in the 1970s.

Royal Palm Breeder Patricia Hill with P. Allen Smith

Looking ahead, plans are underway to readmit the Buff turkey in the future. It was a variety first admitted into the original 1874 Standard. By 1914, the Buff was dropped due to the limited number of breeders and the lack of these varieties’ presence in shows. The HPC supported Zane Graham with the procurement and transport of a flock in New Mexico to his Fall Fire Farm in Arkansas. Like the Chocolates, genetics of the Buffs will be placed with qualified breeders in the future.

HPC board member Dr. Keith Bramwell and P. Allen Smith officiated the awards ceremony at the National Turkey show, presenting award ribbons and premiums from the Heritage Poultry Conservancy for champion, reserve champion and best display of birds.

"The Ohio National and the Heritage Poultry Conservancy are already in discussions for the 2020 show as it relates to heritage turkeys and other breeds with needs,” said Smith.

Work by the Heritage Poultry Conservancy can be followed on Facebook’s Chicken Chat or going to the website heritagepoultry.org

Livestock diversity fading, risking food supply, group says

American Veterinary Medical Association

Livestock Diversity Fading,

Risking Food Supply, Group Says

Livestock genetic diversity is fading, with up to one-quarter of livestock breeds lost or at risk of disappearing, according to a recent paper.

Among poultry, upward of 79% of breeds are at risk of extinction.

The Council for Agricultural Science and Technology, a nonprofit organization that promotes farming sciences, published a paper in September that calls for efforts to protect genetic material that could help animal populations adapt, aid research, and fill specialty markets. The most effective conservation efforts combine living populations that can adapt to disease and other challenges and cryopreserved genetic material that can restore lost bloodlines, the paper states.

"In the face of the mounting depletion in genetic diversity among livestock species, there is an urgent need to develop and maintain an intensive program of sampling and evaluation of the existing gene pools," the paper states. "Genetic diversity can be preserved through living populations or cryopreserved for future use."

Roast Heritage Turkey and Gravy

New York Times

Roast Heritage Turkey and Gravy

By Kim Serverson

Heritage turkeys can be tricky to roast; the flesh is firmer than that of a supermarket bird. P. Allen Smith, the Southern cooking and lifestyle expert from whom this recipe is adapted, suggests a day in a brine sweetened with apple cider and then roasting the bird on a bed of rosemary. Roasted giblets and a chopped hard-boiled egg add texture and depth to his country-style gravy. “The eggs and giblets make it a little more rustic and a little more interesting,” he said. “It’s the gravy that saves that dry turkey.”

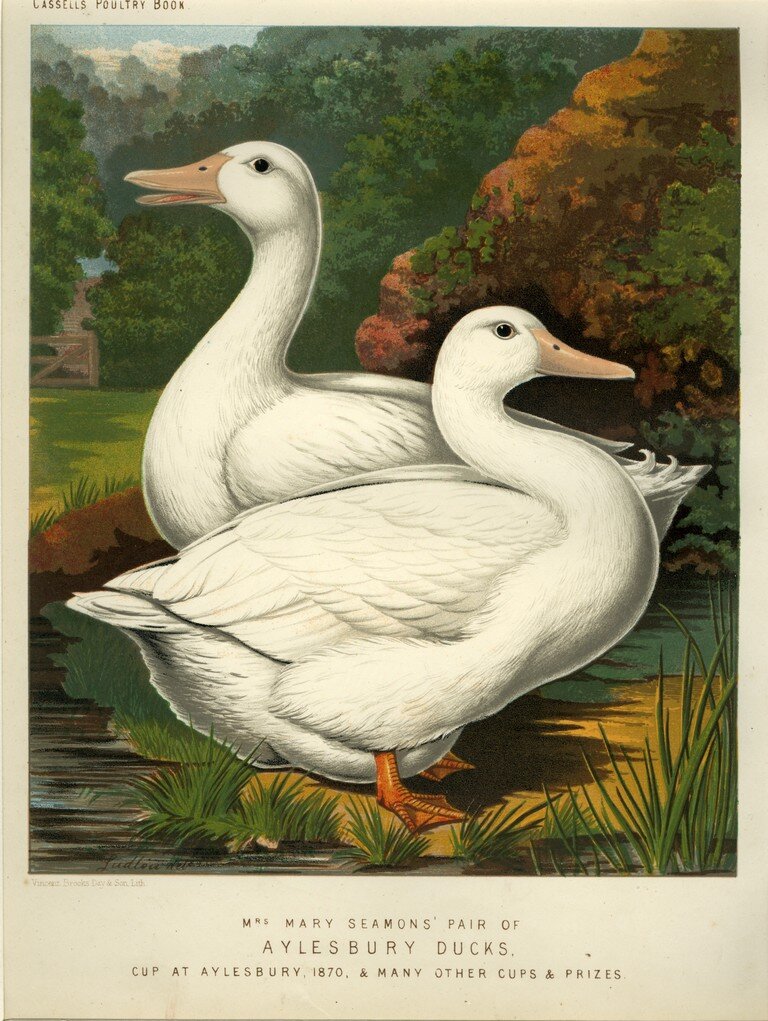

Aylesbury Duck

Aylesbury Duck

The Aylesbury is a duck of English origin bred primarily for meat production. In fact, at one time in that country it was more popular than the Pekin and in some places is still grown commercially to this day. This breed is unique because the color of the skin is white and the bill is pale apricot as opposed to most other breeds of duck which have yellow skin and bills. They are only found with white feathers and lay eggs with white to tinted greenish-white shells. The Aylesbury was recognized in the American Poultry Association's (APA) Standard of Perfection in 1874.

Standard Weights

Old Drake: 10 lbs.

Old Duck: 9 lbs.

Young Drake: 9 lbs.

Young Duck: 8 lbs.

In general, the Aylesbury is a large rectangular shaped duck, with a long body that is deep and moderately wide. The back should be horizontal, long and straight with as little an arch as possible. The stern is deep and should be nearly dragging the ground, and there should be close to a 90-degree angle from the end of the stern as it swings up to the tail. The breast is fairly wide and should be very deep. The breast then leads into the keel, which is deep and should nearly drag the ground. This keel should be long, straight, and free from cavities and should run clear through to in-between the legs. The head and neck are moderately long and refined with a bill that is long and should have a straight topline. The plumage is pure white and should show no sign of creaminess or any other color. The bill is a pale flesh color that approaches white with legs and feet that are orange and the eyes are blue.

Many very early writers of poultry first called the Aylesbury the English White but in the early 1800s their name was later changed to Aylesbury. The name Aylesbury comes from the town of Aylesbury, in Buckinghamshire England, where it was developed as the type best suited to the requirements of the London meat market. In England, it was regarded as superior to all other ducks as a market and table duck, thanks to its white skin, relatively small fine bones and well-fleshed carcass. English duck growers particularly valued them for producing "ducklings" which were ducks slaughtered at seven to nine weeks of age. They were also prized as being early breeders and reaching sexual maturity rather quickly.

Despite being introduced to American poultry keepers several years before the Rouen, Aylesbury never gained much favor or attention in the U.S. For many years they had an established position as one of three breeds of ducks most popular for the table. But after the introduction of the Pekin, the market duck growers in this country abandoned the Aylesbury. Their objections to it were that it was not hardy under the conditions of duck growing in this country and that it was too difficult to dress clean without tearing the skin. These faults were not noticed in England, because the climate is milder and duck growing has always been a "cottage" rather than a farm industry, and the English meat market did not demand that ducks be picked perfectly clean. As the Pekin grew in favor here in the U.S. the Aylesbury all but disappeared. But thanks to those people who used them as exhibition birds the Aylesbury was kept alive, although in small numbers.

Despite their lack of popularity, there have been and are several good quality strains of Aylesbury ducks. However, the Aylesbury remains very rare and is almost always underrepresented at most of America's shows. This is a breed that is in desperate need of more supporters.

Caution should be taken when conditioning Aylesburies for show. In order to maintain the white skin and bill color, the birds should be kept out of sunlight. Otherwise, their feathers, bill, and skin will develop a yellow cast. Feeding additional corn should be avoided as well as green feed such as grass, lettuce, or other fresh produce. This will also be important if you want to produce a white-skinned carcass for the table. In addition to this, be sure to provide them with plenty of water to bathe in. Being a white duck, their feathers will stain easily if they do not have regular access to bathing water. Further precautions against stained feathers can be taken by providing a well-drained area for the drinking water, a layer of gravel or a wireframe to place the water container on is a good way to prevent muddy areas. Another thing that should be done is to give them plenty of clean dry bedding.

Aylesbury ducks have had a reputation of being weak, poor layers and with poor fertility. This is largely untrue; in a well-bred strain, they are as productive and fertile as any breed of duck. Typically one drake can easily service three or, at the most, four females and maintain good fertility. If fertility does become a problem, providing them with swimming water to mate in can help larger drakes mount the females more easily. It is a matter of breeder selection to keep vigor up in any strain of poultry and this is no different from the Aylesbury. As with all heavy ducks, however, care should be taken to avoid overweight birds. Overweight birds do tend to have poor fertility and being too fat can lead to egg production problems. It is a good idea to allow them adequate room to exercise and avoid feeding excess feed and excess corn.

In general, the Aylesbury makes a fine bird for a home flock of ducks. They make good show birds thanks to their easily bred white color pattern and a well-bred duck with its massive size, large block-shaped body, and straight profiled, and graceful head makes for a bird that will catch anyone's attention. For those who wish to just raise their own duck meat, the Aylesbury is an excellent choice thanks to their large size, fast growth rate, and white skin and feathers.

Prepared by Michael Schlumbohm and Keith Bramwell, Department of Poultry Science, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Works Cited

Robinson, John H. Popular Breeds of Domestic Poultry. Dayton: Reliable Poultry Journal, 1924.

The American Standard of Perfection Illustrated: A Complete Description of All Recognized Breeds and Varieties of Domestic Poultry. Burgettstown, PA: American Poultry Association, 2010.

Sheraw, Darrel, and Loyd Stromberg. Successful Duck & Goose Raising. Pine River, MN: Stromberg Pub., 1975.

Grow, Oscar. Modern Waterfowl Management and Breeding Guide. N.p.: American Bantam Association, 1994.

Andalusian Chicken

Andalusian Chicken

Andalusian Chicken

The Andalusian (Mediterranean class) is a non-sitting egg-laying breed that lays a white egg and has white skin. It is only recognized in Blue and it was admitted to the American Poultry Associations (APA) Standard of Perfection in 1874.

Standard Weights

Cock: 7 lbs.

Hen: 5.5 lbs.

Cockerel: 6 lbs.

Pullet: 4.5 lbs.

In size and type the Andalusian is intermediate in stature between the Leghorn and Minorca breeds. Andalusians are a larger framed somewhat angular bird. The comb is single and the earlobes are medium-sized and white. This single comb should lop over to one side on mature females while standing erect on males. The back is long and moderately broad and it slopes from the shoulders to the tail. There is a moderate break at the junction of the tail and back with the tail being long, well spread, and carried at an angle of 30-40 degrees. The breast and body are well rounded and carried rather high in front with the legs being rather long.

The color of a well-bred Andalusian is very striking and also difficult to breed. The ground color is a slaty blue with each feather laced in darker blue approaching black. The comb and wattles are bright red and the shanks and toes are dark blue, the bottoms of the feet should be white.

The name Andalusian is a bit of a misnomer. In 1879 Harrison Weir visited the southern part of Spain, where the district of Andalusia is located, and inquired about the Blue Andalusian chicken. To his surprise, the bird he was looking for was mostly unknown. So it is assumed that this breed has no special connection to Andalusia Spain. However, there are two other accounts that blue colored chickens were found in other parts of Spain. Granted it is not uncommon to find blue colored birds in mixed flocks where both black and white birds are found, so it is still not out of the question that the original "Andalusian" came from Spain. Most likely, the breed was first exported to England via Cadiz, which is in the province of Andalusia. This gave the English breeders the idea that they were common in Andalusia.

Mr. John Taylor, who later became well known for his Andalusians, imported the first Blue Andalusians from Spain to England in 1851, where only white "Spanish" had been previously known in England. These blue birds were incidentally very difficult to find. Of the 12 birds that he bought only three were representative of a pure Andalusian. He then crossed these birds with his original stock and this was the foundation of the Andalusian breed in England. However, not all blue "Spanish type" chickens descended from this cross.

The chickens called Andalusians in the middle of the 19th century were generally described as "gray" in color and were considered a variety of Spanish. In England, blue chickens were also obtained from crosses of Black and White Minorcas and in some parts of England the Andalusian was called the Blue Minorca. The reason for calling them Minorcas comes from a similarity in shape and accounts of pure Minorcas occasionally throwing white and blue offspring. In addition to using Minorcas to produce blue chickens, the Spanish breed was also used. There is one account of a breeder crossing a white Andalusian and a Black Spanish and the resulting offspring were described as a "pigeon blue". There must have also been some confusion between the Minorca, Andalusian, and Spanish, and the names were probably interchanged between the three breeds so it is sometimes unclear as to which one is actually being discussed. Later when the breed became more established, it is likely that any blue chicken could have been called an Andalusian. Over time though the Andalusian was bred as a unique breed and it eventually developed characteristics that made it readily distinguishable from Minorcas and Spanish. The first Andalusians were shown in America around 1850-55. However, it is not known exactly when they were first brought here, or whether those first birds were imported under that name. Much like in England, these first Andalusians shown in the United States could have been "made" from crosses of Black and White Spanish, or Black and White Leghorns, or they may have only been called Andalusians because they matched a description of birds called Andalusians by English authors, but no one knows for sure. What is known though is that in later times Andalusians were both imported and "made in America" and more than likely the Minorcas and Spanish were used to cross on Andalusians to increase numbers and to "make" an Andalusian. Eventually, though a unique standard shape and color were identified and applied to all Andalusians.

The Andalusian is an excellent egg producer of large white eggs. At one time they were believed to be better layers than either Spanish or Minorcas. There are some old records from the 1890's of Andalusians laying up to 230 eggs a year, with the egg weights reaching up to 30 ounces per dozen. And thanks to their larger size the extra cockerels were also somewhat valued as a meat bird. As far as temperament, Andalusians are somewhat active and consequently are good foragers.

The breed would be decidedly more popular were it not for the instability of the blue color. Because of this tendency, interest in Andalusians is largely among fanciers to whom the blue color is so attractive that they prize the breed in spite of the large production of off-colored specimens. The standard color requirements originally called for an even shade of blue, but the tendency to a darker lacing on each feather was so persistent that lacing was made a requirement.

One of the reasons that the Andalusian is difficult to breed is because of the genetics of the blue color. When two blue birds are mated together approximately half of the offspring will be blue, with approximately one-quarter black and another quarter "splash". Splash refers to a bird that is mostly white with a lot of gray or black markings randomly scattered throughout the plumage. Often time's breeders will use a black mated to blue to try and get the lacing back or to darken the shade of blue. Likewise a splash could be used to lighten the ground color; however, not many breeders do this. When breeding Andalusians, or any blue variety, a lot of birds must be raised to produce a sufficient number of offspring in order to get a few good blue colored birds. For this reason, this breed is not suited to someone who doesn't like to cull or who doesn't have the facilities or means to hatch and raise a lot of chicks.

Bantam Andalusian

Both the APA and American Bantam Association (ABA) recognize the bantam Andalusian (single comb clean legged class) and, like the large fowl, they are only recognized in Blue. Shape and color requirements are exactly the same as for large fowl. The bantam sized Andalusian is believed to have originated in England.

Standard Weights:

Cock: 28 oz.

Hen: 26 oz.

Cockerel: 26 oz.

Pullet: 24 oz.

Prepared by Michael Schlumbohm and Keith Bramwell, Department of Poultry Science, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Works Cited

Robinson, John H. Popular Breeds of Domestic Poultry. Dayton: Reliable Poultry Journal, 1924.

Brown, Edward. Races of Domestic Poultry. Liss: Nimrod Book Services, 1985.

The American Standard of Perfection Illustrated: A Complete Description of All Recognized Breeds and Varieties of Domestic Poultry. Burgettstown, PA: American Poultry Association, 2010.

Bantam Standard for the Breeder, Exhibitor, and Judge. 2011 ed. Kansas City: Covington Group, 2011.

Appenzeller Spitzhauben Chicken

Appenzeller Spitzhauben Chicken

Silver Spangled Appenzeller Spitzhauben

The Appenzeller Spitzhauben (not an APA recognized breed) is a relatively small European breed developed for egg production. Commonly known simply as Spitzhaubens, this breed lays a white shelled egg and has white skin. This breed has just recently begun to have a more serious interest in their breeding and preservation. In the United Kingdom and in several European countries this breed is recognized by their associations but they are not recognized by the American Poultry Association (APA) in the US. However, some efforts are underway to standardize them and a breed club has been formed with this effort in mind. This breed occurs in several varieties but the Silver Spangled is the one with the most followers and is the most common variety of the breed.

Proposed Standard Weights

Cock: 4.5 lbs.

Hen: 3.5 lbs.

Cockerel: 3.5 lbs.

Pullet: 3 lbs.

As stated earlier, this breed is not yet recognized by the APA in the United States. However, the Appenzeller Spitzhauben Club of America has adopted the United Kingdom's standards as the proposed standards for submission to the APA. The following is a brief summary of the proposed description for shape and color. The body should be moderately long and well-rounded giving the overall impression of walnut shape. The breast is carried high causing the back to slightly slope from the shoulders to the tail. The tail is long and well spread and should be held at a right angle to the back. The shanks are medium in length with the most striking feature of this breed it’s head. The comb should be V-shaped and the nostrils are cavernous like those of other crested breeds, however, the crest is very different from the crest of a Polish or Houdan. In the case of the Spitzhauben, the crest is medium in size and should stand erect and slightly forward rather than falling to the sides and back of the head. The plumage color and pattern are about the same as the Silver Spangled Hamburg with each feather ending in a distinct black spangle and the remainder of the feather being white. The beak should be bluish and shanks should be slate blue and the earlobes should be white.

The early history of the Spitzhaubens is somewhat of a mystery. It is generally believed that they originated from the canton of Appenzell in Switzerland. Spitzhaubens, or at least birds similar to them, have been known in this area since the 1600s. They are believed to have been formed from the crossings of Brabanter, a Dutch breed, Crevecoeurs, and La Fleche. The Spitzhauben was originally kept by the monasteries where they were valued as a hardy foraging breed that laid a decent number of eggs. At first, it was only these monasteries that kept them but eventually, the breed made its way into the hands of local farmers. For many years the breed never left Switzerland and unfortunately, the breed had dwindled in numbers until very few remained. It wasn't until the 1800s and early 1900's that any were seen outside of their homeland. When this began to occur it helped the breed by increasing its numbers and it steadily increased in population. However, the conflict of WWII almost wiped it out completely.

This is where the modern and well-documented history of the Spitzhauben really begins. In 1953 Kurt Fischer, from Germany, imported some Spitzhaubens and began to breed them in earnest. He was instrumental in getting the Spitzhauben accepted to the German poultry standard and many German and Dutch breeders can be credited for reviving this breed. It wasn't until 1978 that the first Spitzhaubens finally made their way to England.

In the late 1950s, Dr. Albert McGraw had a German friend who brought a few dozen Appenzeller Spitzhauben eggs to America for him to hatch. This was the beginning of the foundation flock of Silver Spangled Appenzeller Spitzhauben in the U.S. Recently other breeders have imported more birds directly from Europe to add to the gene pool of the birds already here in the U.S.

The Appenzeller Spitzhauben in this country still needs a lot of work in order to get them to where they could receive serious consideration for acceptance by the APA. First and foremost the type needs to be worked on and set to achieve reasonable uniformity across the breed. The shape of the crest also needs some modifying as many crests of Spitzhaubens tend to be more Polish-like in shape, being large and round. This is probably due to the fact that many Spitzhaubens in this country were crossed with the Silver Polish in order to broaden the gene pool and to increase numbers. This has had a detrimental effect on crest shape and color. The color of these crosses tends to be more toward lacing rather than spangling. Also, many unsuspecting buyers have purchased "pure Spitzhaubens" in hopes of getting a good bird and in reality what was purchased was nothing more than a mere cross with other breeds. When deciding to breed Spitzhaubens breeders should be aware of this fact and not purchase birds that have had Polish blood added to them or have a program in place to breed back to the original standard description.

Silver Spangled Appenzeller Spitzhauben

In terms of color, the Spitzhauben has a long way to go in order to reach the same high level of perfection of spangling that the Silver Spangled Hamburg has achieved. In time though, with serious and dedicated breeders, this breed should be able to achieve these goals and become a more uniform and better quality show bird.

Most keepers of Spitzhaubens keep their birds for their unique appearance rather than for intensive breeding for breed characteristics. If the breed is to make real progress in the world of standard-bred poultry more serious breeders need to work toward a common goal of creating an attractive show quality bird.

In temperament, the Spitzhauben is very active and tends to be a little flighty. These traits, however, are what make it a good foraging breed. If this breed is to be contained they will need a high fence or one with a cover to keep them from flying out. Wing clipping can also be employed to keep them grounded if one does not wish to show them, however, this can make them more vulnerable to predators that may find their way into the birds' enclosure.

Bantam Appenzeller Spitzhauben

Like the large fowl, the APA does not recognize a bantam Appenzeller Spitzhauben. However, they do exist in Europe and the American Bantam Association does recognize them on their "inactive list". The bantam version was first created in the Netherlands in the 1980's. There, and in other places in Europe, it is found in several varieties including silver spangled, golden spangled, black, and chamois.

Prepared by Michael Schlumbohm and Keith Bramwell, Department of Poultry Science, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Works Cited

"Appenzeller Spitzhauben.": Breed Savers. N.p., n.d. Web. 28 Feb. 2014

"History." The Appenzeller Spitzhauben Society of Great Britain. N.p., n.d. Web. 28 Feb. 2014.

"Spitzhauben." Greenfire Farms. N.p., n.d. Web. 28 Feb. 2014.

"Standard." The Appenzeller Spitzhauben Club of America. N.p., n.d. Web. 28 Feb. 2014.

Brahma

Brahma

Dark Brahma

The Brahma (Asiatic class) is a heavy breed that was traditionally raised for meat production. They lay brown shelled eggs and have yellow skin. From reports in some of the earliest literature, this breed holds the record for the second-largest standard weights with mature birds as large as 18 pounds. They are recognized by the American Poultry Association (APA) in three varieties; Light, Dark, and Buff.

Standard Weights

Cock: 12 lbs.

Hen: 9.5 lbs.

Cockerel: 10 lbs.

Pullet: 8 lbs.

Overall, Brahmas are a large heavy boned breed with a pea comb and very small wattles with the females displaying a dewlap between the wattles. The heads of Brahmas are large and very broad with characteristic "beetle brows". The body is moderately long, wide, and very deep. The back is level with a moderate sweep up to the tail with the shanks and outer and middle toes being feathered.

This breed is most remarkable in that it was produced in India from a cross of Malay and Cochin and was almost immediately brought to America. Furthermore, the breed was developed and perfected in America and England while neglected in India, and given little attention in adjoining parts of China. It takes its name from the River Brahmaputra, a small stream in Assam, on the banks of which it is said to have originated. As a matter of fact, it was first called Brahma Pootra, but later shortened to Brahma. In its history, the Brahma has also been called Cochin China, Gray Shanghai, and Gray Chittagong.

Interest in the breed, and particularly in the birds with the "ermine" color (white with black points), began with the finding of several such birds on a vessel from Calcutta in New York harbor, in 1846 or 1847. In the same lot, there were also dark gray, red, and brown birds. At various times over the next five to seven years, other importations were received, the stock in all cases displayed indefinite patterns and mixed colors. It was claimed by those who obtained the "light" birds of the first importation that these bred absolutely true to type and color. But, the claim does not seem to be well-founded, according to the Brahma breeders who knew the stock in the 1850's reportedly none of the stock bred true to color. Both "light" and "dark" Brahmas were commonly obtained from "light" colored birds, and occasionally progeny of other colors were produced as well. The birds also had the pea comb of the Malay, the single comb of the Cochin, and any intermediate form. At first, the designation "Brahma" was applied only to "gray" birds. From the beginning, the pea comb was preferred, though as late as the early 1870s some strains still had a single comb. The Brahma was, from the beginning, regarded by many as more desirable than the other large Asiatic types, and the Light Brahma became the favorite in its class, a distinction which it has always retained. Brahmas in America have been bred with moderate foot feathering, which often in poorly bred strains is allowed to become very scanty, while in England they have been bred with much heavier plumage. In early times in America, efforts had been made to popularize modifications of the Brahma type in the form of scantily feathered and bare-legged strains, as well as undersized early-laying "utility" strains. Such efforts met with little encouragement, because large fowl Brahmas are, to most people, more attractive when at least moderately heavily feathered on the shanks and feet; and people who wanted smooth-legged fowls and early maturing fowls had a wide choice of other breeds.

The Brahma is very cold hardy and less susceptible to cold and exposure, surpassing the Cochin in this respect because of its pea comb. It is also, because of its shorter plumage, a little less affected by heat than the Cochin, though the differences in this respect are not great. In regard to temperament and broodiness, the Brahmas are as calm as the Cochin but not quite as prone to broodiness. It is not as prone to obesity as the Plymouth Rock and Wyandotte, and when managed for production, Brahmas are persistent layers, and are often either non-sitters or do not go broody until early summer.

Light Brahma

Light- recognized in 1874

The Light Brahma, as a variety, lays a large brown egg of a uniform medium brown color. In the early days, these qualities set them apart from the Dark Brahma and also from the Cochins. The Light Brahma color pattern was and is one of the most attractive color patterns. This gave it popularity as a market fowl, and this led growers to breed Brahmas to the larger and larger body weights. However, the Light Brahma as we know it today is very different from the original Light Brahma. The first Light Brahmas had white under color and less black striping in the saddle area of the male; the wings also had less black in them than they do today. Today the Light Brahma has black striping in the hackle with some black striping in the saddle of the male. The tail is black with the coverts being laced with white. The remainder of the birds' feathers is white with a gray under color. The flight feathers of the wings also have more black with only the leading edge of the feathers being white.

Light Brahma

However, over time the Light Brahma began to suffer in its popularity. This decrease in popularity began when a cock was placed first at a show in New York that had poor type but had excellent color. The publicity given to this bird without criticism of his shape led judges and breeders to give that type the preference over the correct type. The result was that in a few years it became the most common body shape and conformation. Unfortunately, this type was a clumsy, coarse boned, coarse meat type. The Light Brahma's numbers plummeted so low that by 1910 they were seldom seen at the shows where they were once numerous. At the time it was doubtful that they or any of the Asiatic breeds could be revived. The Brahma was rejected by market poultry-men who began to substitute extra-large Plymouth Rocks and Wyandottes. However, these did not meet requirements because the number of big Plymouth Rocks and Wyandotte's were too few. Then gradually the old type of Light Brahma came back, but the color was made more difficult to breed through the influence of breeders of the new Columbian Wyandottes and Plymouth Rocks.

Not only was the color pattern made more difficult to achieve, but by increasing the black pigment to get intensity of the color desired in the wing flight feathers the breeders brought so much black into the white sections that the peculiar beauty of the columbian pattern was lost in all but a small proportion of the best-bred specimens. This lead to the demise of the breed as grown for commercial production of meat, however, today it is a very popular show bird with many birds displaying excellent markings.

Dark Brahma

Dark- recognized in 1874

The Dark Brahma color pattern is synonymous with the Silver Penciled Wyandottes and Plymouth Rocks. The males have a silver hackle and saddle with the feathers being striped with black, with the wing bow and shoulders being solid silver. The tail, breast, and body are solid black. Females have a black hackle with slight penciling of gray and laced with white, while the back, breast, body, and wings are medium shade of gray intricately penciled with black. There should be three lines of black that conform to the shape of the feather. Clarity and sharpness of penciling are of the utmost importance.

The Dark Brahma was never used for commercial meat production to the extent that the Light Brahma had been utilized. The difficult color pattern was also harder to obtain through breeding and therefore smaller birds with excellent color patterns were selected as breeding stock. As a result, the Darks are, on average, smaller in body weight and frame than the Light variety. This difference in size was so much, and by the prompting of Light Brahma breeders, in 1883 the standard requirements were revised to set the weights of Light Brahmas a pound heavier than the target weights for Dark Brahmas. But eventually, these higher weights were also adopted for the Dark.

Dark Brahmas, with the breed shape and character of the Light Brahma, are not as common. Until the Silver Penciled Wyandottes and Plymouth Rocks were developed, the Dark Brahma was the only breed of chicken with the "silver penciled" color pattern, and consequently was a favorite with fanciers of that color. The difficulty of breeding the pattern limited its popularity, yet small flocks of Dark Brahmas were quite numerous until other breeds of the same variety were emphasized, then interest in Dark Brahmas declined.

However, the Dark Brahma, as a breed, did experience a resurgence in interest. It had become apparent that silver penciled varieties in the American class would remain a 'fanciers fowl', and those breeders who worked with them with the expectation that they would become popular and commercially profitable realized they were mistaken. This led to a considerable revival of interest in the Dark Brahma, because the triple penciled pattern can be more easily obtained on large birds with broad feathers.