What moves a person to become a dedicated breeder?

Stories about the conservation of breeds can often be dry, if not dull, but more often than not when you get to the passion at its core stories can become powerful and engaging, contagious even. The intention and the goal of supporting threatened breeds is a noble one, but it’s the people along the way that one encounters and the challenges they meet that makes the effort interesting and inspiring.

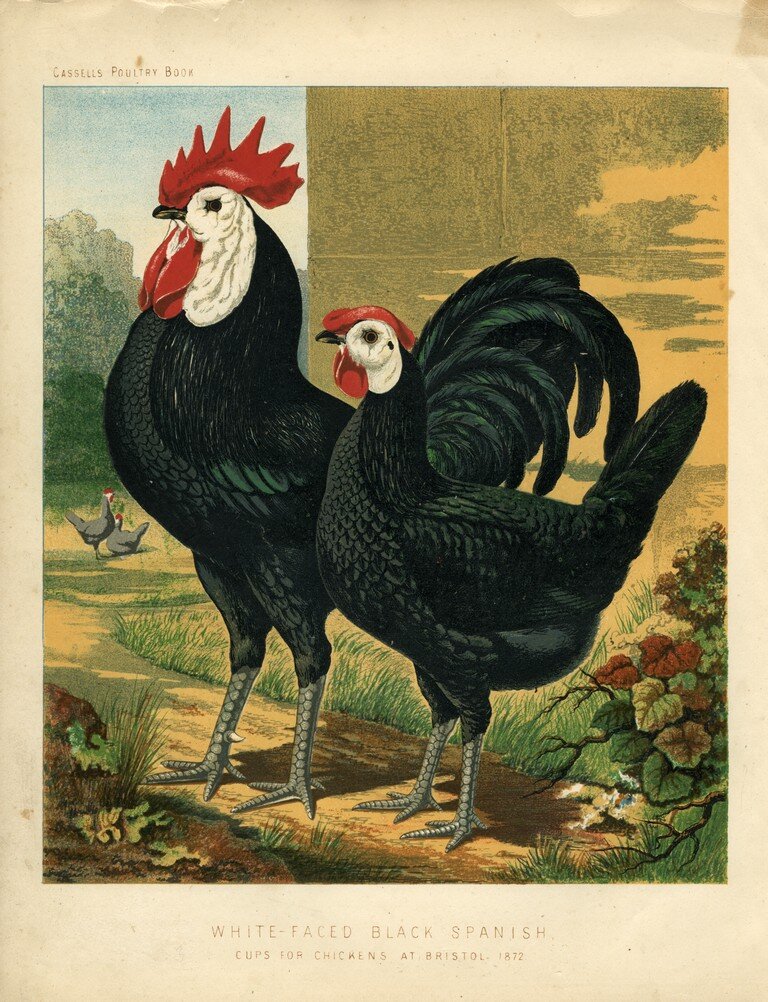

White Face Black Spanish

We began a journey seven years ago looking for White Face Black Spanish at the encouragement of Dr. Keith Bramwell and Frank Reese. It had become clear by speaking to a few APA judges, conservationist that this great foundational breed was in trouble.

We have all heard the reasons about the decline in standard bred large fowl; few breeders are now focused on them, the flocks are small, feed is expensive and fewer have the time and space to focus on them. As a result, viable breeding populations with genetic diversity are diminishing.

White Face Black Spanish chickens are a fowl with ancient origins. It seems certain that they date back to at least the Roman conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, but likely much earlier. Scholars believe Phoenician traders were responsible for much trade and disbursement of goods and livestock much earlier than previously recognized. They became an important foundational breed to the Mediterranean class of fowl and through the mists of time continue to capture us with their striking appearance and generous egg production.

White Face Black Spanish

Seven years ago our flock of White Face Black Spanish came to us at Moss Mountain Farm through Jim Bell, a dedicated and knowledgeable keeper of poultry in eastern Tennessee. When I first met Jim he had kept a flock of large fowl Spanish for 38 consistent years. As he recounted to me, he was a kid always interested in poultry. His father recognized this and told Jim at 9 years old to go through a local poultry show and choose any breed he wanted. Jim did just that. When he saw for the first in his life the strikingly beautiful large fowl White Spanish on display he knew without hesitation in that moment that this was the breed for him. He shared this story with the same enthusiasm he must have had when he first brought birds home. Jim kept Spanish and continued to improve them for the next 39 years. His story inspired and continues to inspire me.

We were fortunate to get to know Jim, for many reasons. His kind, earnest and gentle manner was refreshing. His dedication to the conservation of breeds as well as his family farm naturally drew you into him.

White Face Black Spanish and P. Allen Smith

First, we received a generous batch of Spanish eggs that were picked up and brought to Arkansas by Carroll Moreland on March 1, 2013. Carroll, upon arrival at Jim’s place, was taken by Jim and the care he took of his family’s farm and his flocks. Carroll brought the eggs and enthusiasm for Jim’s work to Moss Mountain Farm. As luck would have it, we had a less than a stellar hatch from the eggs due to an incubator mishap, but what few hatched flourished.

I must admit I was slightly disheartened by the meager flock we had managed to get going with the eggs when Jim on a phone call one day said ‘well, why don’t you just let me hatch you a pen of these’, and he did. That’s how we came to keep Spanish today. Since then we have only outcrossed them once with a male sent to us by Lew Wallace who, at the time, was keeping some of Duane Urch’s line. The outcross was nothing short of explosive.

But, from where do those outcrosses come in the future? And where are the breeders of the future who are so passionate about a breed that they keep them for 39 years? A year after we had a solid flock established Jim shared with me that someone or persons had come on to his farm and stolen his entire flock of Spanish. He had unwittingly shared images of his birds and the location of his farm on Facebook, such as many of us do, and then they were taken from him.

Black Face White Spanish when shocked about the news of Jim’s flock.

Such a loss is bewildering and devastating; heightened by all of the years of dedication. I asked Jim, time and again, if we could get birds back to him to restore his flock. He refused. He had lost something more than the birds themselves. We lost a dedicated advocate of a fragile breed. This was and continues to be very hard to accept.

I give Jim Bell credit for the conservation of a line of such an important breed. Jim is one of those grounded, silent stewards who is a champion that has worked tirelessly to perpetuate a breed out of passion and a deep desire to see the breed prosper. I’m sure similar stories abound. We just need more knowledgeable and committed enthusiasts like Jim, now and in the future.

The Heritage Poultry Conservancy will support a heritage breed initiative at the Ohio National Show in 2020. For more information about the the Heritage Poultry Conservancy join us on Facebook at Chicken Chat.